Gauge Blocks, Phoropters, and Philosophy for Educators

This post was inspired by a Video by Adam Savage: you can see it here

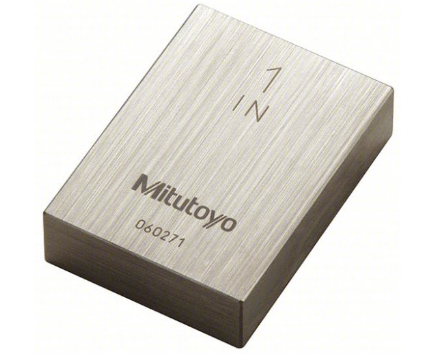

This is a gauge block.

It has a precisely parallel precision ground set of sides. Flat as can be. The amount of precision machining and attention to detail that created this block is extreme. These blocks serve as a kind of master calibration. To provide a greater certainty of the dimension of an object. To help one measure and compare.

This is a set of gauge blocks.

They come in sets and work together by combination to provide reference and calibration for any measure between .05” and 3.9999'“. On their own, in isolation they don’t really do anything. These blocks are used to calibrate a gauge, then the gauge measures some piece of machining (well it’s measured by a machinist using a gauge) which reveals the differences and informs the machinist of any adjustments needed to their work.

The gauges only function when used against something else, inside an existing system of measure, to produce information that can be interpreted and applied. The value in the gauge block is in its capacity to tell a machinist how precise their machining is by providing a reference that differences can be measured against. The machinist may use the blocks to calibrate machines that produce elements of other far more complex constructions but that depend on the reference provided to make sure the other elements fit together. By using these gauge blocks they are ensuring the precision tolerances and creating the best fit. The reference is there to inform practice.

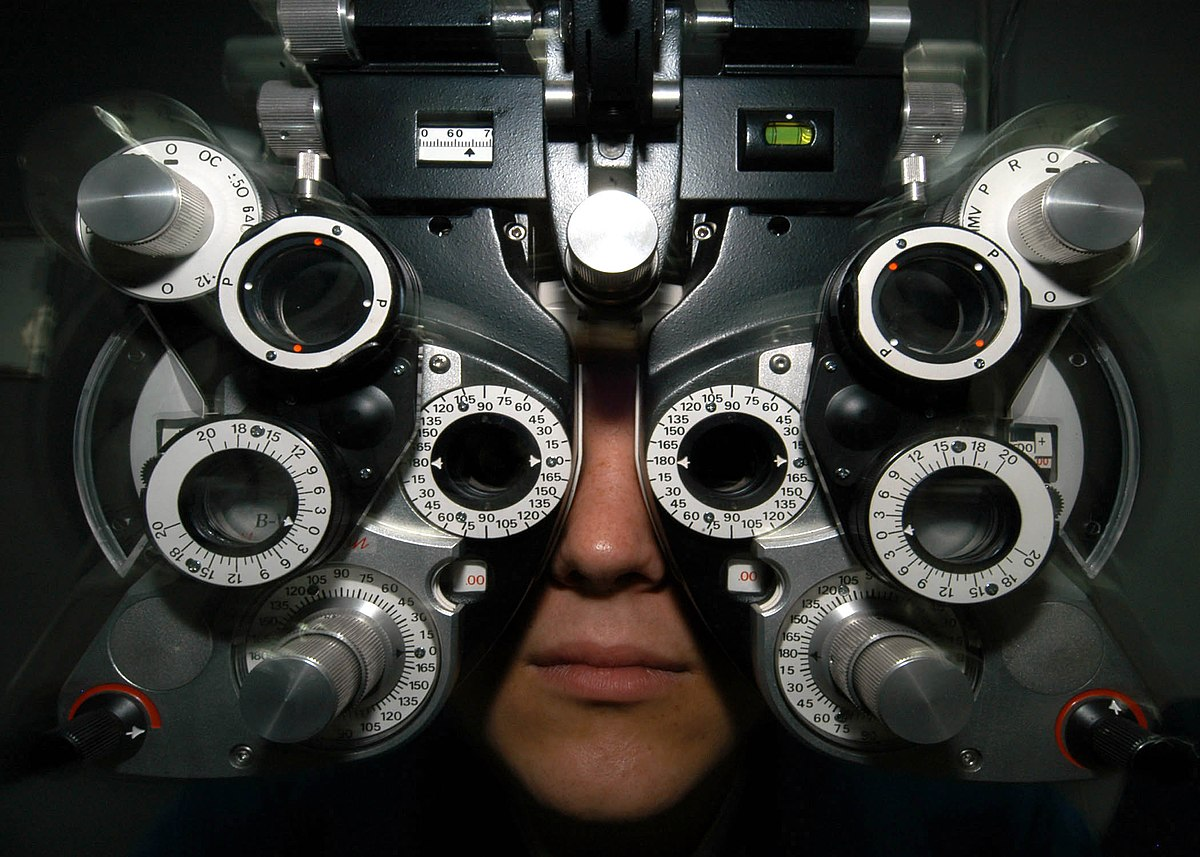

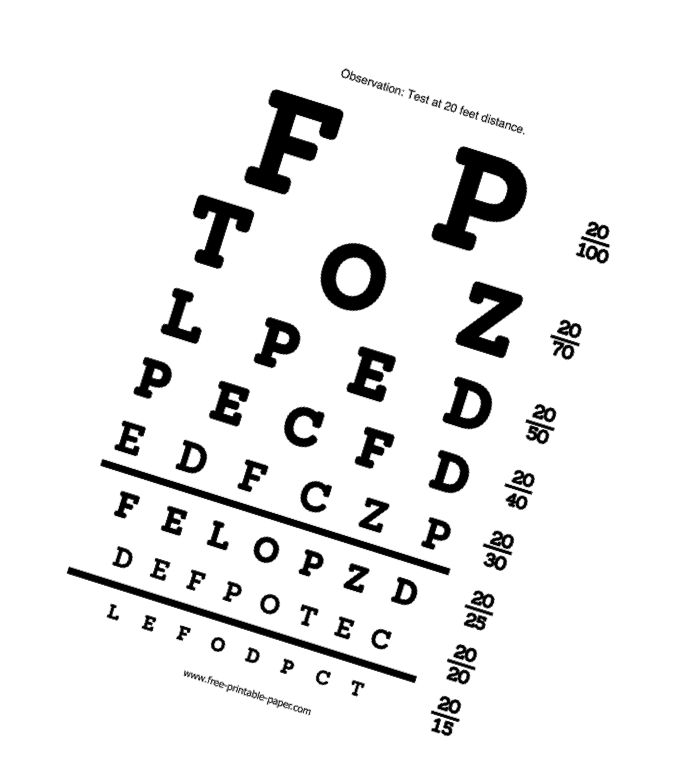

This is a phoropter and eye chart these are used together by eye care professionals to make determinations about the eyesight of a patient. The Phoropter is a battery of lenses that allows for the measure of a patients vision. A patient sits, looking through the phoropter, at an eye chart placed about 20 feet away while the lenses are changed by the practitioner who asks for subjective feedback, asking about clarity of the eye chart. The optical power of the lenses is measured at a certain increment and through changing these lenses and eliciting feedback the eye care professional delivering the examination can determine the shape and kind of lens needed to provide the patient with the best sight. The phoropter needs to be used in conjunction with a subject, the eye chart, without something to focus on the lenses and subjective feedback wouldn’t help to bring clarity and without the lenses the eye chart would never be brought into clearer focus. The reference is there to inform the practice.

The gauge blocks and gauge and the phoropter and eyechart are for me handy. If imperfect, metaphors for the ways in which theory and practice operate for an educator. These tools are used to check and clarify and only work when used together with feedback. The gauge block needs a gauge to measure difference, the phoropter needs subjective experience and the interpretation of the practitioner to work and they both need to be addressing a subject/object of some kind. They work in combination and recombination. The mix of lenses that bring better clarity to the eye chart, the mix of gauge blocks to make up the needed reference to measure against, often it isn’t just one kind of either and if you only had one lens, or one gauge, then their purposes would be defeated. Its in their combination and difference that they tell you what you need to know, that they become useful. They also need someone outside of them to be useful. They need to the optometrist or the machinist to understand apply and interpret what these tools convey. Theory, philosophy, and policy operate the same way for the educator.

This is not a perfect metaphor of course. this is just another conceptual tool that makes an gesture toward meaning that might be useful rather than perfect. But in that spirit of “useful rather than perfect” let me write a little about the use of philosophy and theory for the the educator in the classroom and why I think there is often a disconnect between the two.

The practice of teaching, the actual act of doing it, is a moment by moment affair with concrete concerns like scope, sequence, assessment, remediation, interventions, etc. All that pedagogical content knowledge (Schulman,1986). Not only do you know the content area but also how to teach it and how to teach it to who is in front of you. There is a lot to do and a lot of moving parts and the goals are concrete and tangible. There are assumptions about the ways in which a teacher will teach: What choices they have, what values they’re working from, what the goals are, why they teach what they do as a function of that pedagogical content knowledge- these are all built into the existing context of teaching. These are things that might be trained into a teacher during their education, they might be handed down from the district level and decided elsewhere, they might be arrived at through a career of reflective practice that determines “what works” for you as a teacher. How, though, can you address and refine those practices?

There are practical ways: “ten great ways to teach X” or “ gamify your curriculum” etc. but those things don’t examine teaching as a practice, or give us the distance to think critically about the assumptions at the root of what we do. They give us new and different ways to perpetuate and reproduce thinking. Its the machinist producing a part but not checking the tolerance or the Opthemologist just giving you the same prescription without checking to see if your vision has changed. They produced the part or got you the glasses but clearly the job is half done. To be finished one needs to do more than just the act of doing/ engaging the practice one needs also to engage in a critical appraisal of that work. How do we check that the thinking we’re using is actually worth reproducing? How do we take agency of these choices? What do we use as a reference for our practice? (You might have seen where I am going here, because you’re a smart cookie)

This is where we can engage with theory and philosophies of education and also why we might want to. The roles of theories and philosophies of education is to serve as a reference point that calls the work that we do into a relationship with its assumptions and allows us to reformulate some bigger questions in how we engage in that practice. Its that relation to practice that I think so often is the broken link and I think that there is a way to fix it. Too often teachers engage with philosophy only on its own terms as an artifact of thinking rather than as a tool for application. This is like engaging the phoropter without an eye chart it might be a fun experience to play around with the lenses but its not going to do much for you other that be disorienting and fuzzy. It needs the eye chart and the interpreter of their interaction (the optometrist) to make it useful. The ideas are the tools, teaching is the object we’re measuring and we’re the interpreter of that measure. When we read theory/philosophy without critical interpretive distance and thoughts about application - its a wasted effort. Without those connections and interpretive thinking about what they might mean and how they might function, you only end up with a book report in your brain rather than a tool in your tool box.

To extend our metaphor a little each theory or philosophy is like a gauge or a lens, its something you can use to measure against your own practice and get a little more information about it. Its up to you as the teacher to think about what that information might mean for your practice and if it is useful for your teaching. You can do this kind of thinking by engaging in what I think of as the “affirmative case” for an idea. Engage in a thought experiment while you’re reading and think through what it might mean in practice if it were totally true. Notice any areas you’re encountering where that thought experiment generates tension with your experience/perspective and places where it resonates with your experience/perspective. Then do your own interpretive and evaluative steps- why is this idea in tension or resonance with my own experience or perspective? What kinds of conceptual distance/lack of distance are present between your teaching and thinking and the thinking that is present in the philosophy or theory? What kinds of assumptions, perspectives, or values might account for that distance? Does this idea offer me new ways to contextualize or conceptualize of my own experience/perspective? Why might this person(s) think this thing? How could this idea or elements of this idea be useful to me everyday in the classroom?

These kinds of interpretive processes are active processes. This use of philosophy/theory is instrumental- in that it is a tool. It, through providing another point of reference (like a gauge or lens) asks you to consider your own.

Not every idea is applicable or resonant just like not every gauge or lens is right for every machining project or pair of eyes. Part of that affirmative case might be discovering “if this idea was true, the thing I am using it to evaluate would have big problems” then you need to consider where those problems might be, in your teaching practice , in your interpretation of the ideas as applied to the teaching practice, or in the idea you’re using as a tool. Sometimes the tool isn’t right, no matter how precise the .75” gauge is- its not, on its own, going to help me calibrate a measure for something that needs to be 1”.

Not every idea is complete, or is meant to be complete. Some ideas/theories/philosophies function better when engaged with other philosophies. You might need 2 different lenses in your glasses to see clearly. In the same way, you might need 2 (or more) conceptual frameworks/philosophies/ theories to bring some elements of your teaching practice into critical focus. The .75” gauge won’t help me measure the inch on its own but I can add another block onto it and suddenly it’s indispensable where earlier it might have been useless. The ways you use the tools and the combinations of tools can create effective uses.

Some tools need others to become applicable or functional in ways that aren’t immediately obvious. I might not use a gauge block to check your vision but I might need to use one to calibrate the machines that grind the lenses that sit in the phoropter to check your vision. Without that calibration that is hidden in a web of relation the phoropter wouldn’t work. In this way ideas/theories/philosophies can build on each other and some ideas won’t really be accessible or useful without understanding others. If there’s an idea that doesn’t make any sense to you, there might be a piece of that puzzle missing that needs to be filled in to make it useful. That doesn’t mean its useless, it just means there are other parts to that tool that need mastery first.

Which brings me back to the disconnect that a lot of teachers have talked to me about between theory/philosophy and practice. Being able to name a tool isn’t understanding it and it isn’t using it. One way to bridge the gap between theory and practice is through engaging in the active process of theory as toolbox. In order to make the reference “work” it needs to be measured against something and then the differences need to be analyzed and interpreted. Just looking at the reference doesn’t produce anything, just focusing on the practice doesn’t produce anything. It is only in looking at the information that is produced in examining one against the other that we can have something to interpret and apply. Gauge Block and Machining, Phoropter and eye chart, Theory and practice of education- the reference is there for the practice.